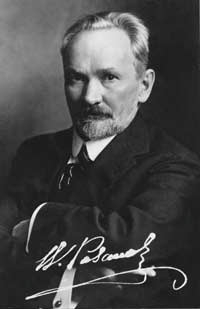

Vassily Vassilievich ROZANOV (20. 04. 1856, Vetluga — 23. 01. 1919, Sergiev Posad Monastery) — is one of the most original, important and yet under-studied turn-of-the-century Russian thinkers. Born into the family of a middle-ranking clerk, he was only five years old when his father died. He was brought up by his mother, nee Shishkina, who had a strong impact on Rozanov's personality. Rozanov's preoccupation with issues of gender and sexuality can be considered to be a result of his mother's extraordinary (for the time) second marriage to a man some fifteen years her junior. In his later years Rozanov considered this age difference to have mystical significance. When he was young, he duplicated the pattern established by his mother in his own personal life. As a student at Moscow University he married a woman who was twenty-four years older than him. This woman was Appolinaria Suslova, the former mistress of Fedor Dostoevsky and one of the first emancipated and sexually liberated women of the generation of the 1860s. She was as sadistic to young Rozanov as she was to Dostoevsky. Although Rozanov and Suslova stopped living together in 1887, she refused to give him a divorce — a state which lasted until her death in 1918. This well calculated strategy cast a dark shadow over Rozanov's personal life; he had to marry his second wife, Varvara Butiagina, in secret, and this marriage, deemed illicit under Church Laws, caused his pious wife a lot of suffering. Their marriage, which lasted until Rozanov's death, caused further inconvenience for the new Rozanov family as their much loved children were considered illegitimate by the Russian Orthodox church. Rozanov's rebellion against the Christian church and the asceticism of Christianity can be seen to have originated in these aspects of his personal life.

In 1882 Rozanov graduated from Moscow University with a degree in history and philology and he started teaching at schools in various Russian provincial towns. His first work was a voluminous tract 'On Understanding' (1886), written in the tradition of academic writing. The work was not a success, and in later years Rozanov commented that had this work been a success he would have become just an ordinary 'philosopher'. Rozanov valued involvement in every day realia and disliked any form of abstract thinking or activities divorced from the physical and emotional needs of human beings. Rozanov's philosophical tract had few readers, but the influential literary critic Nikolay Strakhov noticed this work and reviewed it favorably. It was Strakhov who helped Rozanov to leave the provinces, after finding him a job in the capital city of St. Petersburg. Once he was liberated from the constraints of his provincial existence and the boredom of his teaching job in a school in Elets Rozanov found his true and unique voice and style. This new voice had nothing in common with the impersonal academic narrative of his philosophical opus — rather it was orientated towards more intimate and subjective conversations based on personal human experience. Zinaida Gippius, one of the major Silver Age personalities, in later years described Rozanov's style as a mode of narrative which is impossible to re-narrate. Rozanov's language and technique were the expression of his mind and body imbued with all the subjectivity of experience, and it is probably this subjectivity which made the otherwise very eloquent Gippius feel inadequate in the role of interpreter of Rozanov's prose. Gippius was well aware of the fact that, unlike her and Dmitry Merezhkovsky, who divided the world into the spheres of 'reality and realiora', or super reality, Rozanov drew no distinction between the two. While the Merezhkovskys had an urge to abandon their earthly bodies in their quest for the celestial incorporeality, Rozanov saw in this body the very embodiment of divine will and incarnation.

Although Rozanov was considered to be a highly idiosyncratic personality by his fellow philosophers and writers, he was nevertheless the typical representative of the Russian Silver Age culture. He was also a product of the European fin-de-siecle culture with its preoccupation with questions of human sexuality vis-a-vis biological science and metaphysics. Rozanov's preoccupation with issues relating to sex took place at a time that was characterized by Michel Foucault as rich in discourses on sexuality. Rozanov himself dubbed his own writing as a 'mission of sex', a term which can be interpreted as a polemical statement reflecting the passionate attitude which typified all intellectual activists of his time, whether they were revolutionaries, creative artists or truth seekers of various denominations.

As a man of deeds, Rozanov admired creative energy and despised passivity and inertia. When the Russian Empire came to an end in 1917, Rozanov blamed its collapse on the laziness of the Russian aristocracy and the ruling classes. He also accused Russia's most important cultural institution, nineteenth-century Russian literature, of fostering wrong ideals amongst the Russian people. In his last work, 'The Apocalypse of Our Times' (1918, 1919) he accused such writers as Ivan Goncharov and Ivan Turgenev of teaching Russian readers to limit their interests to the sphere of romantic and unrequited love, instead of giving practical advice and instruction as to how to be proactive, hard working and positive. He equally attacked writers of the critical tradition, such as Nikolai Gogol and the revolutionary democrat Nikolai Chernyshevsky, for teaching Russians how to ridicule and destroy Government and society while neglecting to instruct on how to rebuild and improve society. This work was one of the last expressions of Rozanov's belief in the importance of being involved in everyday life, a belief linked to his love of things physical and corporeal. Rozanov did not privilege the life of the spirit over the life of the body, and in his work systematically destroyed such hierarchies as imposed by the Christian church and Christian thinkers.

What characterized his writing and distinguished it from various contemporary Russian philosophers who tried to resolve the dichotomy between body and soul (such as Vladimir Solovyov) was his belief that there is no such a dichotomy. Rozanov was one of the first pre-postmodernist thinkers to abandon Cartesian dualisms. The most striking revelation was his pronouncement of the sexed body as the body most closely linked to the Creator. Rozanov searched for God in sexuality. If Sigmund Freud saw God as a projection of human sexuality, than Rozanov saw sexuality as a product of God. After the publication of Rozanov's work 'In the World of the Obscure and the Uncertain' (1901), an important symbolist poet and an extravagant personality of the Silver Age, Andrey Bely, described Rozanov's work as 'the flames which burned' the whole generation, and the fire that was set did not mean to burn the flesh, but to elevate it to the status of the soul.

Rozanov's metaphysics spiritualized sex itself, and raised it to the level of a hypostasis. His philosophy in turn can be defined as sexual transcendentalism. In 'In the World of the Obscure and the Uncertain' he wrote that sex transcends the limits of nature, because it is both not natural and supernatural'. Rozanov created his own metaphysics, according to which he identified God with God's creation and proposed a pantheistic faith. At the same time he considered divine presence as corporeal, a phenomenon which man could detect with his senses with the primary sensation being found in sex. He looked for illustrations of this view in the ancient religions. He was attracted to the religions of antiquity because they exalted procreation and child bearing, as well as the love between a husband and wife. He viewed Judaism as the prime example of a religion which views sex as holy, as a tree of life given to people by God himself.

His preoccupation with Judaism lead him to an obsession with the life of contemporaneous Jewry. Rozanov believed that Jews were a genetically unified community which had its roots in the tribes of ancient Israel. As such, he viewed them as physical organisms which retained what he called 'ancient cells' in their minds and bodies. This belief led him to respond passionately to the infamous blood libel case, the Beilis affair. In 1911 a Jew in Kiev, Mendel Beilis, was put on trial for the murder of a Christian teenager. Beilis was acquitted in 1913, and the civilized world turned away from the Russian tsar and a Government which allowed its court to engage in processes driven by medieval prejudice and superstitions. The trial has since been viewed as the last nail in the coffin of the Romanov dynasty. During the Beilis Affair Rozanov produced a number of articles which he published in a book under the provocative title 'Olfactory and Tactile Attitude of Jews to Blood' (1914). In this book he tried to prove that Beilis was able to murder the boy because he was driven by the power of ancient cells which had existed in Jewish bodies from the times of antiquity when humankind practiced human sacrifice. This bizarre stance could not be disassociated from the political implications of a trial that was clearly a manifestation of the Black Hundreds' anti-Semitic policy, which incited anti-Jewish violence as a means to distract poor Russian masses from political revolt against the monarchy. Rozanov's collaboration with the politically ultra-right wing newspaper 'Novoe vremia', and his position during the Beilis Affair, made it impossible for his democratic friends from the Religious Philosophical Society to continue their association with him. Gippius and Merezhkovsky suggested his expulsion from the Society, and for the rest of his life Rozanov's main intellectual companion was the Christian philosopher Father Pavel Florensky.

At the end of his life Rozanov expressed his remorse over his stand during the Beilis affair. In notes written on his deathbed he asked the Jewish people for forgiveness and expressed his admiration for their role and place in history. He also asked for his anti-Jewish books to be burned. Although Pavel Florensky tried to ensure that Rozanov accepted Christianity as the only true religion before his death, there is evidence that Rozanov remained true to his views about the ancient religions of Semitic people. Rozanov maintained that in ancient Egypt and Israel people understood the idea of immortality, and till his last days he believed that the mystery of immortality is found not in Christianity, but in ancient religions. He thus wrestled with Christianity even on his deathbed; while lying in a cold unheated room in the monastery of Sergiev Posad in the midst of post-revolutionary devastation, he dreamed of the hot rays of the Egyptian sun which were for him as much a symbol of immortality as they were a symbol of God's — and man's — phallus.

-=-

by Rozanov:

On Understanding 1886

The Legend of the Grant Inquisitor 1890

Beauty in Nature and Its Meaning 1894

Literary Sketches 1899

In the World of the Obscure and the Uncertain 1901

The Family Problem in Russia 1903

The Russian Church 1906

Around the Walls of the Temple 1906

When Authority Went Away 1909

The Dark Face 1911

Solitaria 1912

Moonlight People 1913

Fallen Leaves 1913-1915

From Oriental Motifs 1915-1919

The Apocalypse of Our Times 1918-1919

-=-

© 2007 Henrietta Mondry, Ph.D., Prof.

University of Canterbury (New Zealand)